|

AN ABANDONED CHILD

Born in 1850 from an affair between an Irish naval officer and a young Greek woman on the island of Lefkada, Lafcadio lived his first two years on his mother's (Rosa Kassimatis') knee, as she waited for Charles Bush Hearn to return from his duties at sea. Rosa and young Lafcadio were moved to Ireland to be cared for by Hearn's dowager aunt. But Rosa, increasingly lonely, homesick, and unstable, left her son in Ireland and returned to Greece. Lafcadio never saw her again. His father eventually abandoned him as well, and he grew into his teens shuttled between boarding schools, until his bankrupted aunt sent him to live with her maid in the slums of London. At 16, he suffered an eye injury which permanently disfigured him- which is why no portrait of him shows the left side of his face. This injury, on top of the insult of neglect and abandonment, left its mark on Hearn's psyche. |

|

AN ETHICAL OUTLAW

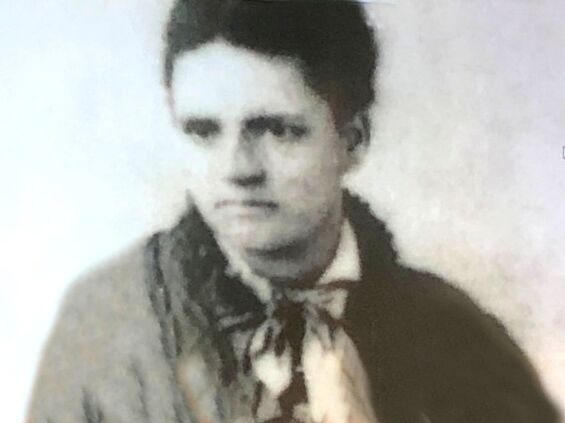

An outcast at heart, Hearn felt most at home with those otherwise crushed under the wheels of industry, and those shunned from 'respectable' society. He chronicled the stories, struggles and songs of the poorest and most vulnerable in the city. He had arrived in Cincinnati shortly after the Civil War, and race relations were tense, to say the least. Undeterred by the taboo against inter-racial relations (he described himself as a "European mulatto"), Hearn fell in love with Alethea Foley, a mixed-race woman who was seen as 'black', and they married (illegally) in 1874. Hearn himself, being of Greek and Irish blood, was barely white himself, but the backlash to this relationship was infuriating. Though they separated after a few tempestuous months, Hearn was seen as breaking a vital law. He was fired from the Enquirer in 1875. This, in addition to the psychological toll of his sensational writings' ever-darker nature caused Hearn to look to more welcoming (and warmer) cultural climates. |

|

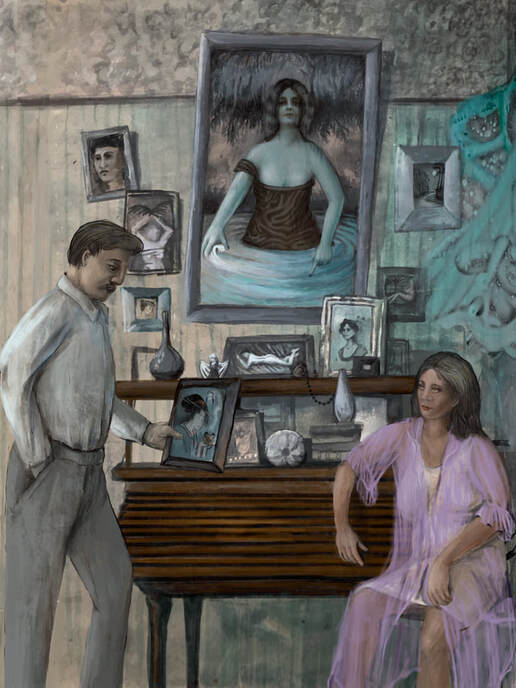

1887 A CREOLIZED TOURIST

In 1877 Hearn boarded a train for New Orleans. As an editor at the Times-Democrat, he had unique access to New Orleans society, and became a frequent guest of literati and other intellectuals. And he continued to chronicle the lives of all classes, often living on a shoestring budget himself. His Creole Cookbook, a set of recipes gathered firsthand, is still celebrated today. He wrote at a ferocious pace, turning out literary criticism, poetry, and even a novel. Though he rose in the ranks of society, Hearn still regarded himself as an outsider on a deep level, and his fragile sense of security led him to abandon friends at the smallest perceived slight. He also saw New Orleans, like Cincinnati, as corrupted by industry, politics and modernization in general, on the decline: "a dead bride crowned with orange flowers". As Hearn began to long for new adventures, his writing began to appear in national journals; an 1887 assignment by Harper's to travel to the French West Indies was a welcome excuse to leave New Orleans in search of a more authentic life. |